Nikolay Mescherin

28.02.1864 - 22.10.1916

Despite his menacing appearance, Nikolai Meshcherin was a lyrical and good-hearted person. His stone-gray beard, which made him look older, did not suit his soft-hearted intelligent character. Easily carried away, he was an educated man who knew the history and theory of art - he collected not only paintings by other artists, but books, and was interested in keeping up with the latest trends. Once he bought a gramophone, and a month later his collection already had 70 phonograph records in it. Meshcherin joked about this in a letter to Igor Grabar: 'Now I'm worried about getting lost in records!'

The son of a wealthy merchant, the founder of the Danilovsky Textile factory, Nikolai Meshcherin had been drawn towards beauty from his childhood. However, his father was against his fascination with painting. He used to say, “Does being an artist sound like a career?” To disobey his father was unthinkable, and Nikolai entered the Moscow Practical Academy of Commercial Sciences. When his father died, the 16-year old Nikolai had to commit himself to the full-scale management of the family business, and he never graduated from the Academy. With the business going well, Nikolai passed it over to his brothers and settled on the Dugino estate. It was time for him to pursue his artistic explorations.

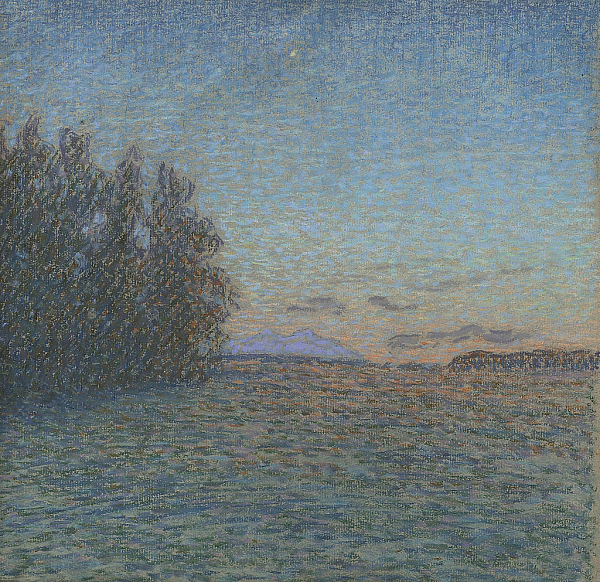

At first, he was fascinated with photography. Later, he created artworks made from dried herbs and flowers. Finally, at the beginning of the 1890s, he took up painting seriously and started taking private lessons. Meshcherin's paintings were first shown at the exhibition of the Moscow Association of Artists in 1899, and his “Aspens in snow” and “Little oak” received positive reviews from critics.

In its popularity as an artists' community, Dugino was soon compared with the famous Abramtsevo estate of Savva Mamontov. Some painters lived there for years. Nikolai Meshcherin entertained his guests with refreshments, open-air painting, and hunting. In the summertime Nikolai's brothers, their children and relatives came to Dugino. They played children’s games, swung on the swings, swam, and played tennis, but the main event was when everyone gathered around the samovar. “A gathering of twenty people around the table was usual, sometimes there were even forty,” Igor Grabar wrote about those tea-party times in Dugino. The samovar was kept hot at the table day and night, when it was covered with comforters on the off chance that guests might want some tea. On warm days these gatherings would move to the glazed terrace. When it was very hot, a table would be set for the artists in the alley of lime trees. "Levitan might well not have made his two paintings of the new moon if the year before he had not seen both motifs in Dugino in Meshcherin's sketches. He studied them thoroughly, carried away by them: "What a wonderful motif. No one has painted sheds, but someone should have done so. Your obedient servant is now busy with painting the same motif,'' - can we believe those words of Meshcherin's friend Igor Grabar? Everything is possible.

Becoming an artist in mid-life, Nikolai Meshcherin devoted the last sixteen years of his life to art. He has gone down in the history of art as a bright character and an artist of note. It was natural that at Diaghilev’s Paris exhibition, five landscapes of Nikolai Meshcherin were hung next to paintings by Serov, Benois, Vrubel, Korovin, and Grabar.