Пожалуйста, учитывайте это при планировании посещения.

С 13 сентября музей работает в прежнем режиме

Для посещения постоянной и временной экспозиции достаточно приобрести единый входной билет

От провинциального купеческого города 1880-х до динамично развивающейся столицы 1930-х — такой ее видел журналист и писатель, такой ее увидят и посетители выставки «Свой человек. Владимир Гиляровский»

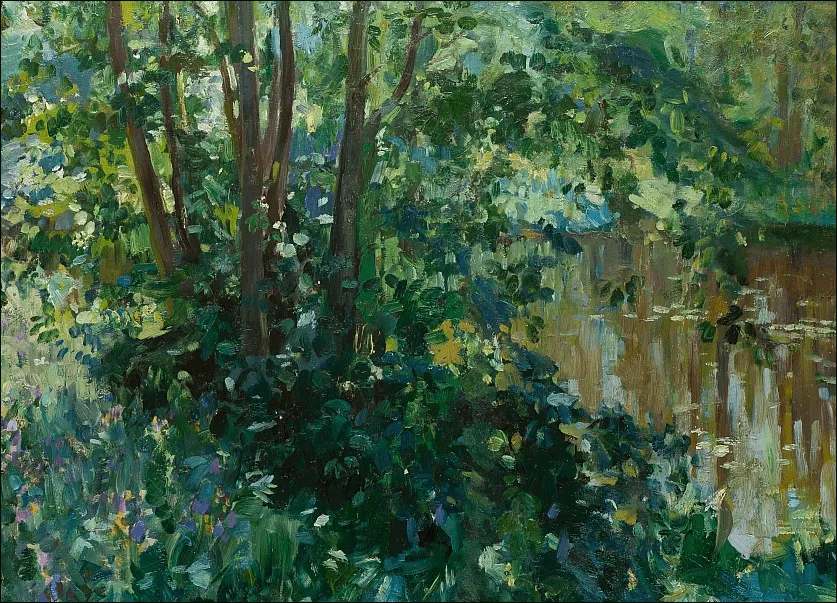

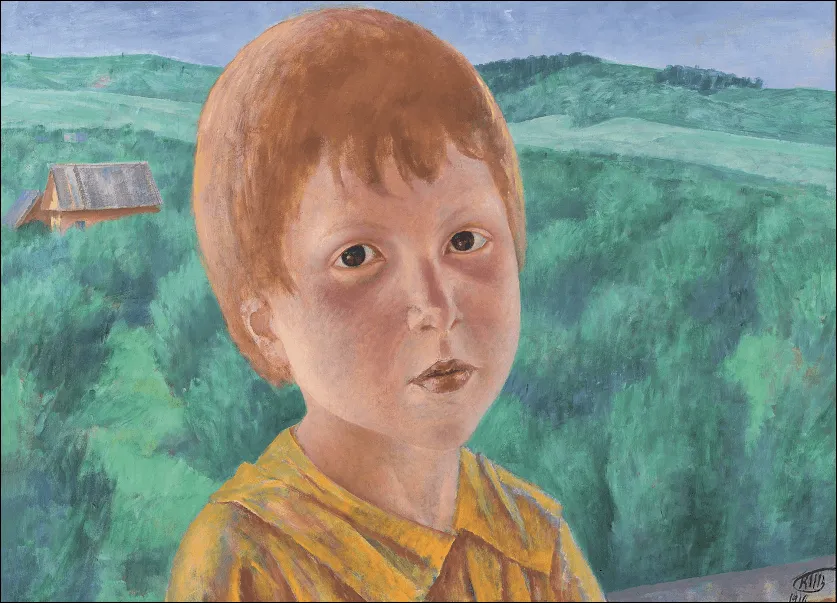

Наполненные светом и воздухом полотна русских художников-импрессионистов

Подпишитесь на рассылку — будем присылать вам только самую полезную и интересную информацию

.jpg)

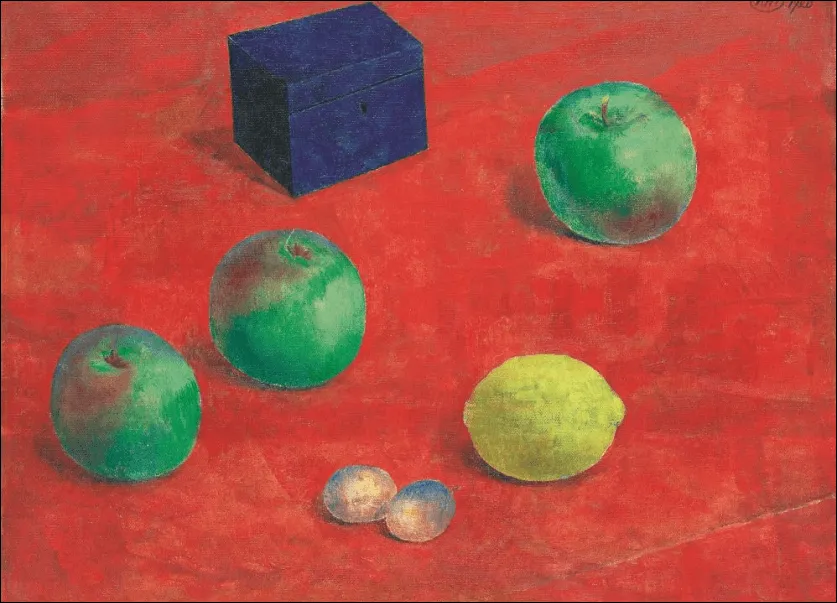

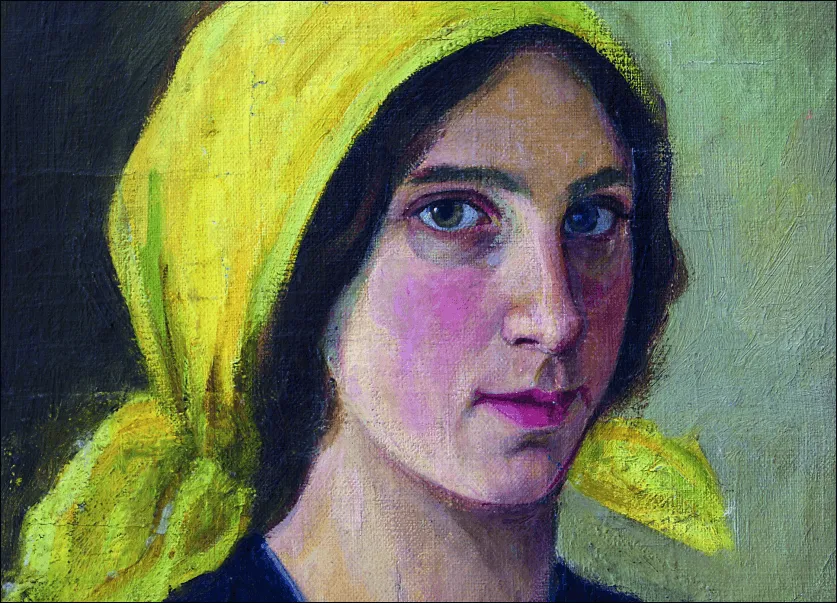

Фовистские работы европейских и русских художников начала XX века

_(1).jpg)

Спецпроект Matisse Remix — воображаемая мастерская лидера фовистов

Долгожданный разбор специфики русского импрессионизма, титульная выставка музея

Работы мастеров одноименного творческого союза и погружение в атмосферу Серебряного века

Картины со страниц первого отечественного глянца — журнала о светской жизни «Столица и усадьба»

_(1)_(1).jpeg)

Модные образы, светские ритуалы и блеск повседневности

Первоклассные работы художников, чьи имена утрачены в вихре событий XX века

История первой российской галеристки, куратора и коллекционера Надежды Добычиной

Развитие стиля на примере работ из коллекции Музея русского импрессионизма

Лучшие студенты Императорской Академии художеств едут навстречу современному искусству Европы

Мир гармонии и грёз в работах мастеров Саратовской школы живописи рубежа XIX — XX веков

Творчество художника, которого сравнивали с Врубелем — только не мятущимся, а умиротворенным

Увлекательное сравнение — как художники изображали себя и какими их видели современники

Удивительная пластичность образов знаменитого певца в его портретах и автопортретах

История масштабной выставки авангарда, случайно забытой в Вятской губернии сто лет назад

Как путешествуют картины, когда отправляются на выставку на другой конец страны

.webp)

Выставка-исследование, посвященная авантюрной попытке показать русское искусство в США

Поразительные истории жизни советских коллекционеров сталинской, хрущевской и брежневской эпох

Персональная выставка художника-импрессиониста, арт-консультанта самого Морозова

1910-1920-е глазами художника, который не боялся увидеть перемены вокруг себя

Первая в России масштабная экспозиция испанской живописи рубежа XIX — XX веков

Драматичные судьбы друзей-художников, полные трагических поворотов и творческих подъемов

.jpg)

Ретроспективная выставка художника Николая Мещерина

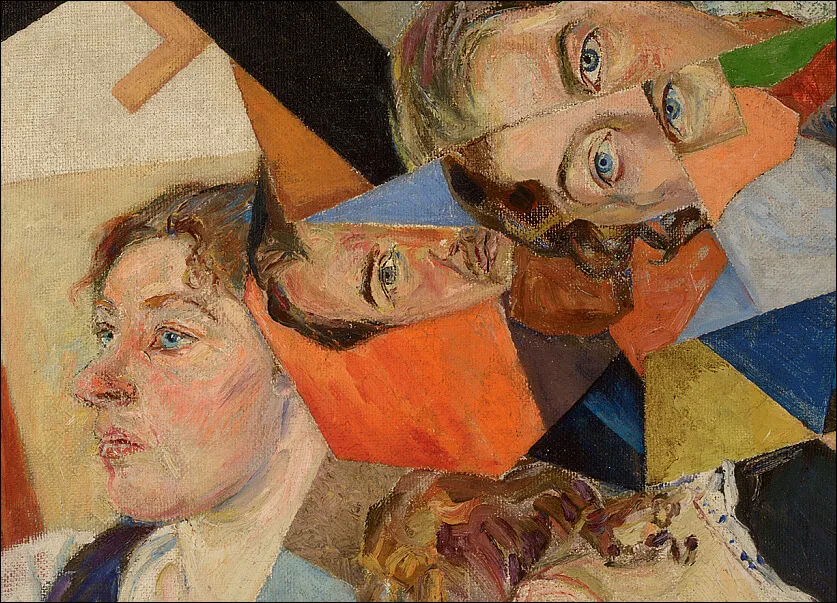

Калейдоскоп метаморфоз «отца русского футуризма», художника и поэта

Начало экспериментов: импрессионистические работы русских художников-авангардистов

История русского искусства через призму портретов жен и спутниц художников

Ретроспектива ученика Валентина Серова, импрессиониста, нашедшего свой творческий путь

Первый публичный показ русской живописи и графики из собрания знаменитого скрипача и дирижера

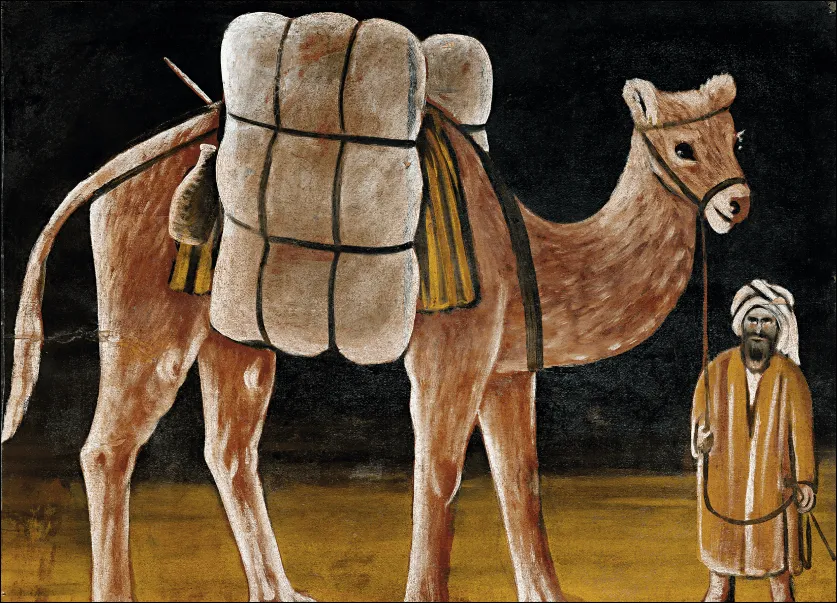

Самобытный вариант усвоения уроков импрессионизма — на солнечных полотнах армянских художников

Незаслуженно забытое и открытое заново творчество яркой художницы эпохи модерна

Проект-размышление современного художника о том, что останется потомкам от нашего времени

Первая выставка музея, посвященная художнику-эмигранту и поклоннику Сислея

До 25 января 2026 года проходят выставка «Свой человек. Владимир Гиляровский» и спецпроект «Пространство технологий».

Вся информация об этом — в разделе «Купить билет» (яркая кнопка в верхней части экрана) или по ссылке

Да, к каждой выставке мы публикуем каталог. Его можно купить в музейном магазине на −1 этаже или онлайн с доставкой. Также доступны брошюры — более компактный и бюджетный вариант издания о выставке.

Сейчас в музее постоянной экспозиции нет — все три экспозиционных этажа заняты временными проектами: выставкой «Свой человек. Владимир Гиляровский» и спецпроектом «Пространство технологий»

Время осмотра зависит от комфортной для вас скорости, но в среднем занимает час-полтора. Аудиогиды к выставкам длятся от 30 минут до 1 часа.